Tenure: helping or hurting?

Once hired on the tenure track as an assistant professor, a faculty member spends five years developing a portfolio to present to his or her department. During the sixth year, the faculty member is evaluated and the Board of Trustees either grants tenure or gives the faculty another year before terminating employment.

Cassidy Ferguson doesn’t pay attention to her educators’ job titles.

While students like Ferguson took courses this year without a thought to whether their teachers hold doctorates, Faculty Senate discussed promotion and tenure at length. The conversation, which lasted an entire academic year, is not over.

Ferguson, a freshman public relations major, said she didn’t know much about tenure, but thinks the concept could be harmful to student learning.

“If a certain number of students don’t like a professor, administration should be able to do something,” she said. “(Administration) can’t if they can’t fire (tenured professors).”

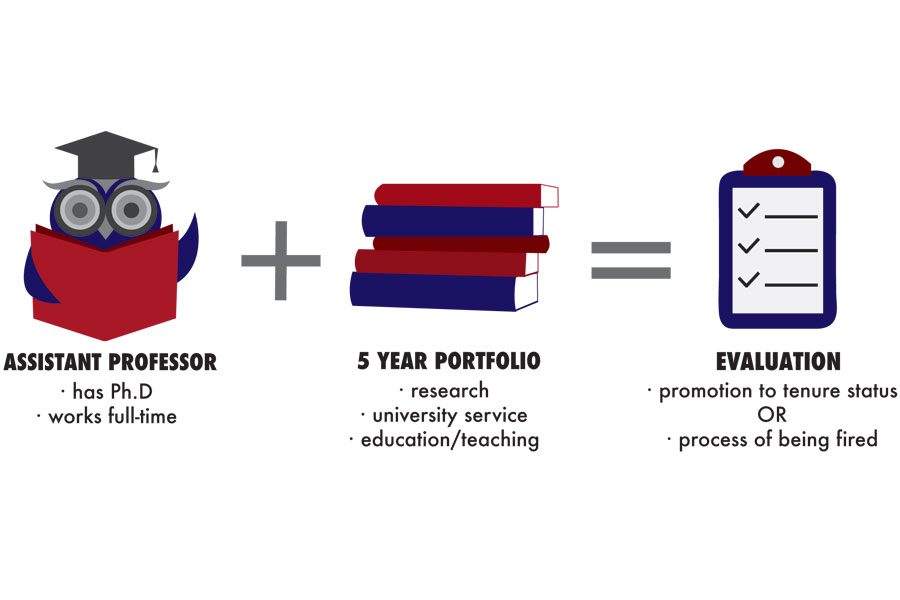

When the university hires a full-time educator with a doctorate, that individual is hired as an assistant professor.

Assistant professors seek tenure, which is essentially permanent job security.

On the tenure track, assistant professors collect evidence of scholarship, research and service for five years. After that period, departments give recommendations to the dean, then to the university committee, provost and Board of Trustees.

If a professor receives tenure during that sixth year, he or she receives a permanent job contract and becomes an associate professor. If tenure is denied, the assistant professor is given a seventh year at the university before being fired.

Faculty Senate’s discussion focused on whether to disband or keep the university-wide promotions committee. The committee remains as is, while the discussion about the tenure process will continue into the 2016-17 academic year.

Ferguson wants her educators to engage with her regardless of tenure or job title.

“If a professor is bad, I’d question if they have a good education,” she said, “but if one is good, I’ll be impressed and not care.”

‘It didn’t used to be like this’

Robert Wuerth considers himself “anti-tenure.”

Wuerth, an instructor of accounting, is in his last semester at the university and said he never had any desire to achieve tenure.

“Once you’re tenured, you could be totally worthless, but (the university) can’t do anything,” he said. “(Tenured professors are) clearly treated differently because no matter how bad they are, they can’t be fired.”

Within his department, Wuerth said career work often matters more than a doctorate.

During his time at the university, Wuerth has seen several professors who, despite having Ph.D.’s, failed at teaching because they had no experience.

“If you have experience in accounting, that’s what students are looking for, not the academic,” he said. “Students don’t care whether you have a Ph.D. or a master’s.”

He said the quality of an instructor isn’t defined by their job title or the contract they hold with the university.

“I wouldn’t want tenure because I’d want to keep the high quality students want,” Wuerth said. “Once you get tenure, you’ve got no motivation. You have increased salary and don’t have to work as hard as before.”

According to the public university payroll, the highest-paid professor for 2014 earned $136,390. Two tenured professors, both from the accounting department, made more money than several associate provosts and assistant vice presidents in administration.

However, the lowest-paid instructor in accounting made $25,800 in 2014, which is only 18 percent of what the highest-paid tenured professor made.

“It didn’t used to be like this, where you have incredible difference in salaries,” Wuerth said. “You bring in a Ph.D. and pay them maybe twice as much, but then they’re horrible teachers.”

Making students enroll, making students stay

Wuerth first worked at the university 20 years ago and retired after 10 years. The Romain College of Business reached out to him for help this past year, so Wuerth decided to teach for one more year.

He said when he came back, he found the accounting program had “deteriorated.”

“When I came here, I said, ‘My gosh, this is bad.’ All the people they bring in have no experience,” Wuerth said. “Students just want to learn from you, and it’s not just talking textbooks. It’s about the real world.”

He said the decreasing trend in enrollment, especially in the accounting department, can be attributed to weaknesses in the hiring process.

From 2014 to 2015, university enrollment dropped 3.6 percent, according to the University Factbook.

The undergraduate accounting and professional services program had 297 students in 2014 and 275 students in 2015, a 7.4 percent drop.

The program’s enrollment decreased 22 percent in the past five years.

“Once students are here, they’ll stay, but they won’t come if the faculty isn’t quality,” Wuerth said. “When professors get tenure, you won’t get the (quality) results, yet you pay that person much more money.”

Nicholas LaRowe, however, said receiving tenure will only enhance his teaching.

The assistant professor of political science is awaiting tenure approval during his sixth year on the tenure track. He said because he’s gotten recommendations from the department chair, the department and the liberal arts dean, he’s pretty sure he will receive it.

“It’s certainly possible that when you get tenure — a lifetime job — you won’t want to work as hard. Any system has ways to take advantage of it,” he said. “But most of us get into this job because we like it.”

As a member of the 2015-16 Faculty Senate and the incoming chair of the 2016-17 senate, LaRowe said promotion and tenure is critical at a university.

“It’s hard to think of anything more important than this discussion,” he said. “I think it’s something we need to keep on talking about as a university.”

He said tenured professors might not receive more respect from students, but there is certainly more respect from other professors and administrators.

“The main reason I sought tenure was academic freedom,” he said. “You can explore controversies and take more risks. I might experiment.”

‘A higher standard’

Paul Kuban said if anything, receiving tenure helped his teaching rather than draining his motivation.

“I’ve discovered that I’ve worked harder the longer I’ve been here,” the tenured engineering professor said. “With tenure comes a lot more responsibility, such as mentoring faculty, serving on committees and taking a leadership role.”

He said tenure was his ultimate goal because of job security.

“In engineering, I’d make a lot more money working in industry than academia, but tenure is something you can never get in an industry job,” Kuban said. “It’s a trade-off — a lifetime job for a lower salary grade.”

He said another good reason for offering tenure at a university is the push it creates for excellent faculty.

“Tenure forces early faculty to work to a higher standard in order to earn it,” Kuban said. “They put in an extra effort to gain that tenure, and I don’t know that that happens at places with no tenure track.”

Hiring and keeping faculty with doctorates is necessary for the engineering program’s quality, Kuban said.

“We probably wouldn’t be accredited without faculty with terminal degrees,” he said. “The accreditation board looks at that.”

Kuban said students probably don’t take note of their instructor’s job titles.

“I don’t think it matters to the students whether the teacher is an instructor or a professor,” he said. “But I do think they respect when a certain instructor has education in their field that lends credibility to what they’re teaching.”

Provost Ron Rochon said tenure provides “great recognition” and opportunities.

He said when he was in college, he knew little about tenure.

“I think it would be wonderful for students to learn about the tenure process,” he said. “I believe in discovery and for students to ask healthy questions about what’s going on.”

He said the university is having good discussion about the future of promotion and tenure, and he hopes all faculty will be part of the conversation.

“Tenure is not for everybody,” he said. “At the university, we have lots of different titles and different ranks. (All faculty) are worthy and respected. They are full-fledged citizens of the community.”