After being on display in the Kenneth P. McCutchan Art Center/Palmina F. and Stephen S. Pace Galleries* from Feb. 17 to March 21, “Unmasked: The 1935 Anti-Lynching Exhibits and Community Remembrance in Indiana” has moved to the Evansville African American Museum. It will remain on display there until May 31.

According to Alex Lichtenstein, professor of history at Indiana University, the exhibition was “in some ways, an exercise in history.”

While the 1935 art exhibitions created by the NAACP and the John Reed Club

(which was essentially the Communist Party, as Lichtenstein puts it) inspired the exhibition, Lichtenstein explained that certain events, like the murder of George Floyd and the creation of the Equal Justice Initiative Memorial in Montgomery, Alabama, redirected it.

“That’s when we started thinking about how black communities wrestle with the trauma of this experience,” said Lichtenstein. “That brought in another layer of artworks, and then we started thinking very hard about current efforts around the country, but in Indiana in particular, to memorialize this violence and to make people aware of it today.”

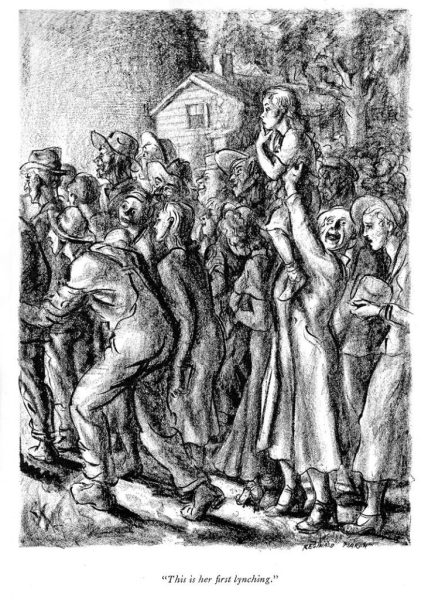

Phoebe Wolfskill, associate professor of American studies, African American studies and African diaspora studies at Indiana University, referenced an artwork by Reginald Marsh when discussing the exhibition.

“They see the lynching that we don’t see, but it’s the idea that she is being introduced to this culture at a young age, and she’s the only one that looks concerned and perplexed,” said Wolfskill.

“Part of what we grappled with as well,” said Wolfskill, “is how do you let the images speak but also provide the viewer with enough text to give them background, because the imagery is really disturbing, and so they need some caution. They need some information, but we also don’t want to overwhelm them with text at the same time, so that the images do their work as well.”

“In the NAACP exhibition, there’s a lot of focus on the black man as a Christ-like victim. In the Communist Party work, there’s more sort of institutional critique that our courts are so sullied,” said Wolfskill.

They also contemplated how they could go beyond addressing only victims.

“There’s a real fatigue with seeing violation of black bodies, which we see still nowadays,” said Wolfskill. “We have to have the information to know how to react, but at the same time, we don’t want blackness to equal death; we need something else.”

Wolfskill mentioned that almost every black artist she has studied has made work on the topic of lynchings.

“What does it mean for the family who was left behind, or how do they carry on? What does that mean in terms of emotional trauma, but just sort of in terms of everyday practical stuff? How do you go through life like this once you’ve lost somebody? So that was part of the framing,” said Wolfskill.

Rasul Mowatt is the department head for Parks, Recreation and Tourism Management at the College of Natural Resources at North Carolina State University, he also holds affiliate faculty status in the anthropology and sociology departments.

“The perspective on violence that I take in my work is from the vantage point of perpetrators and spectators,” said Mowatt. “Thus, I made an emphasis to my colleagues not to make our exhibition a memorialization of the lynched. It is an indictment on lynchers and the efforts of those who were engaged in anti-lynching.”

According to Lichtenstein, during the Marion lynching, a mob murdered two black men and almost murdered a third, James Cameron. After escaping, Cameron would write a book about his experience and open a museum in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. This museum was the only place outside of Indiana that they took this exhibition to and presented it.

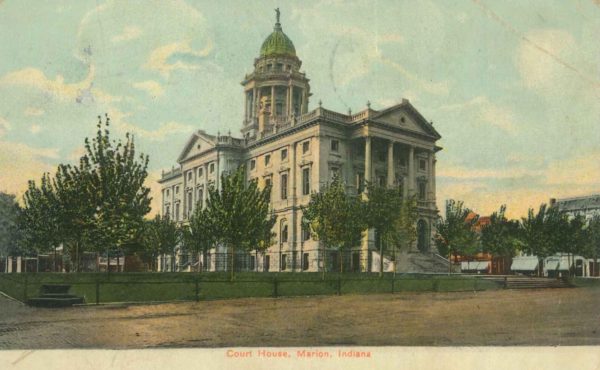

Lichtenstein explains that the Marion lynching did not occur in the backwoods; it occurred on the county courthouse lawn. Visitors unfamiliar with Marion’s history would not see anything to indicate what had happened there.

“I feel, and the people doing this memorial work feel, that what you need is a marker or a monument or a memorial, so that anyone who comes to this town is going to know its history,” says Lichtenstein. “Not to throw shame on the town, but to the understand that this is part of the past, and we cannot move forward in the present until we know what part of the past we have to overcome.”

“For me, the purpose of this kind of exhibit is to prompt more memorial work like that done over in Mount Vernon,” said Lichtenstein.

According to Wolfskill, the most reproduced photograph of a lynching came from the Marion lynching, and this photograph also inspired the song “Strange Fruit.”

She mentioned that after the reconstruction, black people were not allowed to relocate to Indiana, and “the black population has always been discriminated against here.”

Something that Wolfskill found interesting was traveling with the exhibition because of the local history that they encountered. She specifically mentions a photography studio in Terre Haute, Indiana, where Frederick Douglass had been photographed.

“That conversation about racial justice had been brought to that city by someone as famous as Frederick Douglass again and again,” said Wolfskill.

But there is something to be gained from continuing the conversation within Indiana.

“Where the past focused on the passage of anti-lynching legislation, the present (particularly in Indiana) has been focused on the acknowledgement of buried history, reconciling inaccuracies in the public record (changing coroners’ notes), and developing support and space for memorials,” said Mowatt.

Mowatt found that funding the exhibition was a challenge, with materials included in it being difficult to acquire.

“In many cases, we had to spend personal funds as well as research funds to acquire the rights or copies of materials, paraphernalia, etc. that was present in the first, more permanent exhibition,” said Mowatt.

But for Mowatt, who has studied lynching since around 2000, “seeing a present-day exhibition dedicated to those who fought against lynching in order to inspire others to look into this history is its own reward,” said Mowatt.

“One of the things we always emphasize is that memory and remembering, remembering is resistance,” said Lichtenstein. “Remembering and insisting that this part of the past has to be made visible if we are actually going to build a better world.”

According to Lichtenstein, Berlin, Germany, inspired the exhibition in terms of “memory of horrific deeds.”

“The city is saturated with this horrific history, and they don’t shy away from it,” said Lichtenstein. “It’s not a city filled with wonderful, beautiful monuments, it’s a city filled with monuments and memorials of atrocities. But, for me, that was always very powerful.”

Another influential location was South Africa, an area whose history Lichtenstein has studied extensively. He found that South Africa’s memory culture was trying to “make the difficulties of the past, and the abilities to overcome those difficulties, central to the current political culture.”

“The United States has begun this memory work, and there’s lots of great grass roots efforts making it happen, but there’s strong pushback now,” said Lichtenstein. “What I worry about now is that this current government is digging up the Stolpersteine, figuratively speaking.”

*I viewed the exhibition while it was in MACPACE, and no photography was permitted.