We’re not represented

January 25, 2018

In a world where the race conversation grows bolder and bolder, it’s painful to sit in a classroom as the only ethnic minority.

When pursuing a bachelor’s degree at a well-rounded university, one should be able to assume they’ll find a variety of people and experiences to learn from throughout the four-year-or-longer experience.

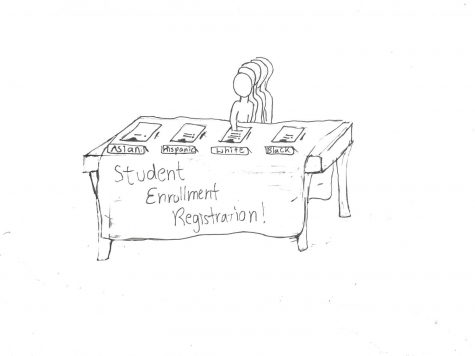

However, time after time, my liberal arts classes have been glaringly lacking in minorities, people who can attest to racial inequality in their everyday lives. Too often in the discussion-based classes, minorities aren’t able to speak for themselves when the students tackle race relations. They’re not even at the table.

According to the USI Factbook, 11.9 percent of students at the university identify as minorities. In the U.S., the census reports about 23.1 percent of the population identifying as minorities. To make it more local, Indiana’s census reports about 14.4 percent.

After being warned about hyperdiversity before coming to the university by more conservative well-wishers, I expected to see more of it in the classroom. I expected the ratio of ethnic minorities to be at least 1:3 or 1:4.

Boy, was I wrong. I silently seethe in my seat as a guy in my seminar class makes a statement generalizing Asian people with one appearance, and wonder if I’d have the guts to say something if there was another person of my ethnicity in the room.

The lack of diversity is a sore thumb when classes try to integrate current events and race relations into curriculum. It’s cringeworthy when there isn’t a black student to share honest opinions and experiences dealing with racism, and instead white students speculate about what these minorities “must be facing.”

I came to college expecting stimulating conversation. But can there be successful conversation if there aren’t enough diverse experiences to go around? It’s certainly not fulfilling to leave class hearing the majority make assumptions about populations and individuals that aren’t there to argue.

The university must work harder in recruiting a diverse student body, and then push all of its students to share experiences and learn from one another. As touchy a subject affirmative action is, it’s necessary to building a student population representative of the general American public. What the university has now is apparently not enough.

Higher education should not exclude minorities from the conversation. If a university fails to intentionally focus efforts on recruitment and retention for minorities, in both faculty and students, colleges implying diversity in thought and worldview is not high on their lists of priorities.

Ultimately, that’s why students are here. I’m not saying the university isn’t trying, but I’m saying it’s not trying hard enough.

It’s imperative. We need everyone in the room.