‘Every intent of being open’

Updated policy introduces new areas for speech, expressive activity

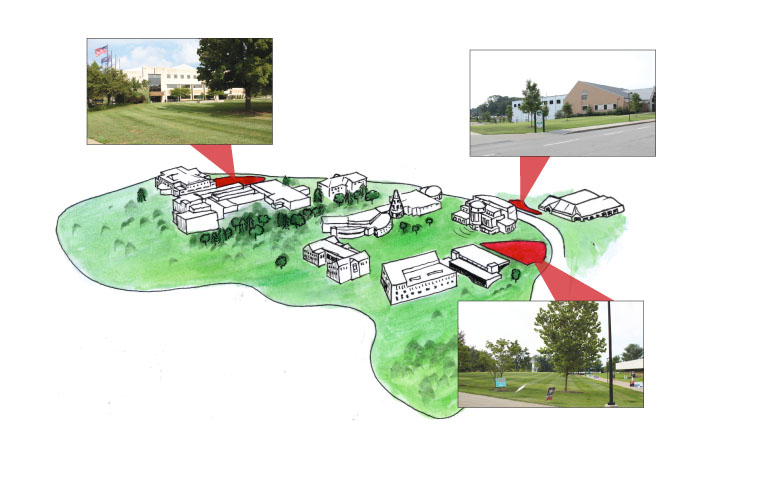

The university has updated its policy regarding areas on campus which are designated for “speech and expressive activities.” The locations are the lawn area south of Rice Library, the lawn area between the Physical Activities Center and the Recreation, Fitness and Wellness Center and the lawn in front of the Health Professions Building. The three areas combined are approximately 1.6 acres of the 1,400 acre campus

Freshman Shelby Heins said having zones specific for free speech wasn’t something she would expect to have on a college campus.

“We’re paying to go here,” the nursing major said. “So our thoughts should be heard.”

As a new student, Heins and several other freshman said they didn’t know about the university’s policy on free speech, which was most recently updated in August.

The updated policy, which is labeled F9 in the University Handbook on USI’s website, eradicates what was known as the Free Speech Zone and creates three new zones for “speech and expressive activities.”

Because of the Fuquay Welcome Center construction, the original Free Speech Zone between the Performance Center and the Orr Center will no longer be usable. A committee led by Kindra Strupp, director of Marketing and Communications, decided to replace that zone with three new locations.

The locations are the lawn area south of Rice Library, the lawn area between the Physical Activities Center and the Recreation, Fitness and Wellness Center and the lawn in front of the Health Professions Building.

Whether student organizations or unsponsored speakers, the university requires individuals or groups seeking to use these spaces to get permission through the Dean of Students Office.

“I don’t like that you have to ask permission,” Heins said. “But maybe it makes sense if the speech gets to a point where it’s offensive.”

While several students The Shield spoke with brought up the concept of college being a more “safe space” than the “real world,” Dean of Students Bryan Rush said he hopes students’ views are challenged on campus.

He said that might mean they take offense to something said in a protest, and that offense could benefit students in the long run.

“I hope students don’t live in a bubble,” Rush said. “We encourage them to be the ones who regulate the conversation if they’re offended.”

Rush said while the concrete changes in the policy are the new zone locations, he and the committee that worked on the policy spent much time on the “philosophical” portion explaining the university’s intent in having the policy.

“While we don’t limit free speech, it changes when it turns into a personal attack,” he said. “Our central focus is to have the ability to have civil conversations. That doesn’t necessarily mean ‘nice’ all the time.”

Permission is required for anyone to use the three designated areas, and Rush said even if that was not clearly articulated in the older policy, the process of registering to use spaces has “always been in place.”

Maintaining the ‘decor’

Last October, senior Lauren Abney held a silent counter protest in the Free Speech Zone after Students for Life hosted an anti-Planned Parenthood demonstration in the Quad.

While student organizations can use the three designated areas, university-registered groups are eligible to schedule areas such as the University Center or the Quad, which would have more traffic than the three zones.

Because Abney and the two other students in her demonstration were not affiliated with a campus organization, they were limited to just the Free Speech Zone.

Abney said the process of registering to use the area wasn’t clear to her.

“I wasn’t given specific directions to contact DOSO until after I talked to a second professor,” Abney said. “They didn’t respond until the morning of to tell me I was supposed to be escorted to the Free Speech Zone.”

Although the process was unfamiliar to Abney, she said she didn’t feel any of the procedure was unfair.

Abney said she hopes with three areas for free speech as opposed to one, more organizations or students will use them.

“I believe people that learn (here) are allowed to express and challenge ideas and beliefs, so long as it is done appropriately,” Abney said.

While the policy of registering was unclear for students like Abney, Strupp said “there has always been a registration policy.”

The process of reserving space on campus was not mentioned in versions of the free speech policies, but the policy is articulated within the Student Handbook.

If students seek to use the zones, information needed for proper use and scheduling is spread between the student and university handbooks.

Registered student organizations and sponsored speakers have the opportunity to use the Quad. Anyone seeking to use any of the areas must register with the Dean of Students Office and/or scheduling services.

Both documents are accessible from the university website, but they are on different sections of the website without link to each other.

Strupp said it wouldn’t be a bad idea to consolidate the documents, but it would take time.

By following the scheduling policy, Strupp said the university can properly notify Public Safety if there needs to be officer presence at a demonstration.

“We need to know who’s planning on coming to campus,” she said. “It is certainly not based on what a group wants to say.”

She said when picking three new places on campus for “expressive activity,” the committee she headed needed to find visible locations without obstructing traffic or university functions.

“We wanted to provide more opportunities with three locations, areas at which we can converse,” Strupp said. “There’s no magical number to three, it’s just what we could find on campus.”

While she and Rush said the multiple locations would open up more scheduling times and prevent double-booking, neither said actual scheduling conflicts for the previous zone led to the creation of three.

Strupp said while the previous area was called the “Free Speech Zone,” the new areas are not referred to as such in the policy and shouldn’t be.

“(‘Free Speech Zone’) is a lot more limited, and that’s not what we’re looking for,” she said. “We want students to know that we are an advocate for free speech. The university in no way wants to limit or dampen speech, but we do need to maintain the decor of the university.”

Regulating vs. restricting

Sophomore Jessica Coleman said the new locations don’t have the same traffic as the previous Free Speech Zone.

“It’s not as ideal for organizations or speakers,” she said. “They can’t get their words out as much.”

Coleman said the entire idea of free speech zones on a college campus is “odd,” but the policy for registration isn’t “bad.”

“Since the university owns the property, they can regulate what goes on,” the sophomore biochemistry and German double major said. “It’s like, ‘my house, my rules.’”

The Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) evaluates schools across the nations and policies possibly affecting free speech on college campuses.

Based on nine policies, FIRE gave USI a red light rating for its policies concerning free speech as of Aug. 25.

However, FIRE published an evaluation today applauding USI for the language used in the most recent policy update. FIRE states the strength in the update lies in the university’s endorsement of the University of Chicago’s policy concerning free speech.

FIRE considers Chicago’s document as the “gold standard” in evaluating free speech policies on college campuses.

A red light rating means USI has “at least one policy that both clearly and substantially restricts freedom of speech.”

Strupp said the university was aware of FIRE’s previous evaluation and considered some of its points in creating the policy update.

“This policy now reflects our university and who we strive to be,” she said. “The language (in the policy now) is what this organization recognizes as green light in their vernacular.”

The University of Chicago is referenced as a source at the bottom of the first page of USI’s policy.

Strupp said she hopes people with different opinions feel welcome on campus.

“These policies are living documents, and as our world changes, we’ll need to look at these policies and reflect those changes,” she said. “We have every intent of being open as a university. The campus is open for speech.”