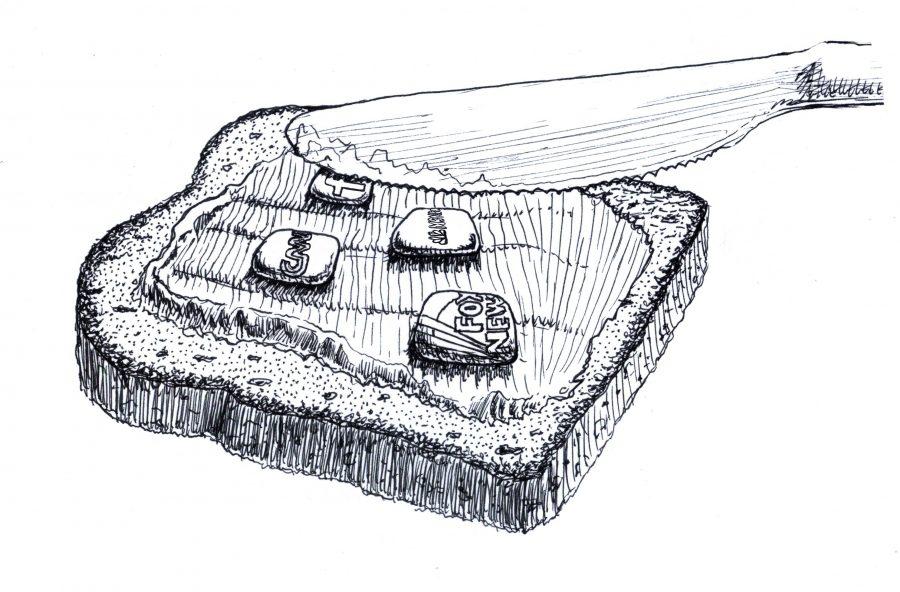

Politics and social media

Illustration by Philip Kuhns

Illustration by Philip Kuhns

Seated behind the screen of his Apple laptop, Brandon Parker clicks between web browser tabs.

The content of the pages is almost exclusively political—articles and statistics he Googled during a USI Democrats meeting.

“I have an embarrassing amount of news and political apps,” the freshman finance major said, pausing to pick up his iPhone. He scrolls between pages, counting. “I have 13 in total. Not including ESPN, of course.”

Since he began following presidential candidate Bernie Sanders in August, Parker said he frequently reads his tweets, shares Sanders’ posts and has even tweeted directly to the politician – and got a response back.

“I like it because there’s no filter between what Bernie says and the news,” he said. “It’s coming straight from the source.”

According to a 2014 Pew Research Center survey, 16 percent of registered voters follow candidates for office, political parties or elected officials on a social networking site—a 10 percent increase from the 2010 midterms. The number is only expected to increase.

Post persuasion

The survey found that 35 percent of registered voters who use social media to follow a political candidate say a major reason is it makes them feel more personally connected to a politician or group.

“People aren’t sending self-addressed stamped envelopes into campaigns anymore—they’re sending a Facebook message or a direct message on Twitter,” Republican political strategist Rory McShane said. “The inconvenience of connecting with a representative or someone running for office has been eliminated.”

McShane works for RedRock Strategies, one of the largest campaign firms in the West.

He uses a third-party app introduced last year that targets Facebook ads based on a user’s home address. McShane can look up the addresses of citizens who voted in the last Republican primary and match that information to their Facebook account.

“Social media ads used to be scattered,” he said. “You would post something on your page and hoped people liked it and shared it and that the right people saw it. From beginning to end, there’s much more control over it now.”

With so much sharing, liking, posting and retweeting about politics, it’s easy to assume social media has helped increase voter turnout.

Benjamin Russell, assistant professor of communications, said not so fast.

Russell, who teaches a graduate political communication class, said many of his students assume social media has spurred users, especially young adults, to become more active and engaged in politics.

According to the most recent Pew Research Center Political Fact Sheet, 25 percent of social networking site users say they have become more active in a political issue after discussing it or reading posts about it.

Yet the authors of a 2015 meta-study concluded that increased social media use did not affect people’s likelihood of voting or participating in a campaign. The findings cast doubt on previous studies which stated social networking sites can have a direct impact on voter turnout.

“At this point, I’m hesitant to say that social media has a direct effect on making people more politically active,” Russell said. “I think it definitely gets people talking and sharing ideas, but it’s hard to say how much this translates into action.”

Campaign managers aren’t the only ones sharing information about political figures.

According to the Pew Research Center, 38 percent of those who use social networking sites “like” or promote material related to politics or social issues that others have posted.

“For the first time, a candidate doesn’t have to do as much work to get their message out,” Russell said. “As long as the post or message is creative, people will share it.”

‘It can spread like wildfire’

But in a digital age, can a tweet become a weapon?

When Republican presidential candidate Ben Carson promptly left Iowa following the caucus Feb. 1, CNN reported on it. Almost immediately, a Ted Cruz staff member tweeted that Carson had dropped out of the race and would not be participating in the New Hampshire primary.

The rumor was false, but Carson’s numbers the next day were dismal. Cruz, on the other hand, won the caucus.

“Even if information is false, it can spread like wildfire on social media,” said Robert Glenn, a liberal arts instructor and Owensboro city commissioner. “It didn’t really matter that Cruz apologized the next day for the tweet. The damage was already done.”

Always considerate of historical implications, Glenn said social media has changed how people discuss and inform themselves in a “big way.” People can communicate with friends and peers, but they can also communicate with political figures faster, and vise-versa.

When candidates use social media and non-traditional news outlets, voters can form a parasocial relationship with them, Glenn said. They feel like they know the political figure personally. More importantly, they feel like they can trust them.

Voters like Parker, who follow political figures on social media, often say they do so because they like getting information straight from the source.

But not every source is reliable. Social media has become a two-way street between voters and political figures, making them more accessible (and more influential) than ever.

“Everyone is human, and anyone can make a mistake,” Glenn said. “But the rapidness (with which) those mistakes can be shared, preserved and analyzed is alarming.”