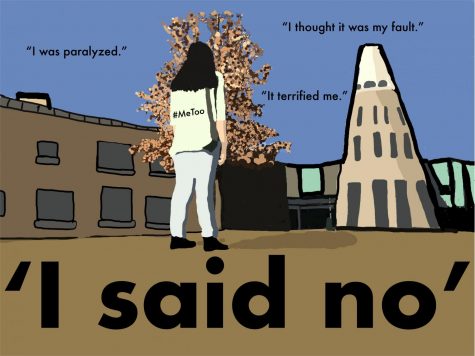

‘I said no’

Students share experiences in light of #MeToo movement

February 13, 2018

Illustration by Megan Thorne

Illustration by Megan Thorne

Tess Whitesell was ready for college when she moved onto campus the fall of 2015—her spark of excitement still bright.

She didn’t know that in a matter of months, she would end up leaving after being raped, bullied and harassed.

‘I do not want to do this’

When Whitesell moved in, there were several days before classes started. She hung out with a group of friends she, for the most part, didn’t know prior.

The group of four boys and four girls decided to get alcohol and gather in O’Bannon Hall, one of the four residence halls on campus. They stayed in one of the rooms in the two-bedroom layout, leaving the door unlocked so they had access to the common room in between. Whitesell realized she needed a phone charger, and went to fetch one from the other bedroom.

“I used my flashlight to get the phone charger, and then I heard the door shut and a lock,” the former student said. “I turn around, and there was a completely naked guy standing in front of me. He grabbed my hands and pulled me back to the bed… I was like, ‘What is going on? I don’t even know your first name; I do not want to do this.’”

Whitesell said she tried to convince him he shouldn’t do something he would regret, but he promised he wouldn’t turn into a stranger and would keep in touch with her throughout the semester after they had sex.

He didn’t listen and proceeded to rape Whitesell.

“By the grace of God, after my pants were down and he was forcing himself inside me, someone started banging on the door,” she said. “They realized the door was locked and nobody could get in. I was able to get free from him and went to the door, hysterically crying.”

Before Whitesell could explain what happened, her rapist spun his own story.

“I heard him come into the room and he told the guys, ‘She just blue balled me,’” she said. “As if I made any slight notion that I wanted that to begin with.”

Whitesell called her boyfriend at the time, who was attending a different school, and he started to tell Whitesell that it must have been her fault.

“I was hysterical again,” she said. “When I came back in, all the other girls were gone, except one girl and the guy that just attacked me. He’s doing the exact same thing to her.”

Whitesell said she stopped the guy from going further with the other girl, who was more intoxicated than Whitesell. They left the room as quickly as possible. Whitesell didn’t tell anyone at the university for fear of being punished for the alcohol and making the situation worse.

“We never told anybody, and I still regret that a lot,” she said. “I didn’t know if anyone would be on our side.”

The “friends” Whitesell had just made ended up bullying her for “blue balling” the guy and didn’t believe her when she said it was rape.

“They called me the girl that blue balled,’ or, ‘You’re that bitch, stupid redhead,’” Whitesell said. “I left USI at the end of (freshman) year after I’d gone through so much harassment and bullying from his friends.”

Although the incident prevented her from pursuing a college degree, Whitesell said she’s found power in the #MeToo movement where victims of sexual assault are sharing their stories.

The #MeToo movement started in 2006 when survivor Tania Burke coined the phrase, but the movement gained traction in October 2017 as celebrities started exposing sexual assault in Hollywood, business, and politics.

“I’m really glad the #MeToo movement is here,” she said. “It gives people more confidence to share their stories like I am now. You don’t want to be that one person it happened to, but when you’re one of many, that makes sharing feel a lot better.”

While Whitesell acknowledges the rape wasn’t her fault, she said she might have been able to stay at school if she had talked about what happened sooner and didn’t try to internalize it.

“I did go and see a campus therapist,” she said. “I mentioned that I had been raped, but I didn’t go into much detail or tell her where it happened. I kind of wished (the therapist) would’ve asked more about it. I feel like it’s important for them to be curious about that, especially when it’s a student living on your campus.”

Since leaving school, Whitesell has seen a therapist and been able to process the experience.

“I don’t care what people say now,” she said. “People can say whatever they want after they read this, but I’m sharing my story. I know what happened, I understand it and I’ve come out stronger.”

While Whitesell doesn’t intend on returning to college at this time, she’s currently in the process of applying for a flight attendant position. She’s different than she was when she was a freshman undecided major—she’s looking forward to the rest of her life.

“It’ll be really important for me to educate not only my daughters on how to handle this kind of situation but my sons on how to behave in a way that’s always respectful to women,” Whitesell said. “There is no other form of consent other than the word ‘yes.’ Anything else means ‘no.’”

‘No one owes you anything’

Like Whitesell, the senior psychology and English major Katie Biggs has found a supportive community in the #MeToo movement. She said she’s experienced sexual assault and molestation from a young age, but an instance in 2011 is the one that’s impacted her the most.

“Before the movement, I knew that what I had gone through wasn’t normal,” Biggs said. “But I had this severe fear of victim shaming. But thankfully that did not happen to me. I saw so many of my female friends and family members (post about) experiences that qualify under the #MeToo movement, and to see them using their voices was quite an impactful thing.”

Biggs was sexually assaulted on December 24, 2011, by a male neighbor she knew from high school. He kept telling her he was going to come over, but she said no. He kept telling her that she owed him. When he finally said that he was walking over to Biggs’ house, she decided to come outside to tell him that he needed to leave. He then attacked her.

“I was paralyzed,” Biggs said. “I couldn’t do anything. I just sat in the snow and couldn’t even process what just happened. People couldn’t touch me for months after that.”

Christmas Eve hasn’t ever been the same.

“For a really long time I thought it was my fault,” she said. “He came over to my house, and you think, ‘Oh, well, you went outside to meet him, so you gave him permission. He’s a close friend of yours.’ But it wasn’t okay. I said ‘no’ multiple times.”

For years after the attack, Biggs said her life was going downhill. She engaged in alcoholism, drugs, and self-harm, and she isolated herself from the things she used to enjoy. She attempted suicide multiple times, but she tried to hide her struggles from her family.

When it came time for Biggs to apply for college, USI was far enough from home that it felt like it could be her way out of the pain.

“I drove six hours away, enrolled at USI, and said, ‘This ends now,’” Biggs said. “I really struggled with my addictions my first year. I said I had it under control, but I was still losing my mind.”

Things changed for the better when Biggs started sessions with the Counseling Center on campus.

“It took a while for me to talk about (the attack),” she said. “I had bad experiences when I told people what happened to me as a child and was blamed for it. I didn’t want that to happen again, but eventually, I did end up speaking to (my therapist) about it. I realized it helps to talk about it. The more I keep it in, the more it destroys me.”

After graduating this semester, Biggs plans to take a gap year and move down to Evansville permanently. She then wants to apply to Ph.D. programs in clinical psychology and help others who have had traumatic experiences.

“No one owes you anything,” Biggs said. “You always have the choice to change your mind. People have to realize they have to respect others, and you can’t assume that if they’ve agreed, for one thing, they’ve qualified for something else.”

Alyssia Haymond, a mental health counselor at the university Counseling Center, said consent is crucial to all of these interactions

“Is everyone on board? Is everyone enthusiastically on board? We don’t say no means no’ anymore, we don’t say ‘yes means yes;’ we want enthusiastic consent,” she said. “It should be very obvious that everybody is on board for what is about to happen.”

Haymond said the #MeToo movement shouldn’t only be for female victims, but for men.

“I think that men also need to be able to have a safe place to speak out,” she said. “Men have completely separate issues than what women often have”.

To respond to victims sharing their story, Haymond said that allies should support their friends by validating their experiences.

“It is okay to not be okay,” she said. “Any survivors of sexual assault should know that they are worthwhile, and it is not their fault.”

Sophomore biochemistry major Myranda Thompson at first felt like she asked for what happened to her, but the #MeToo movement empowered her to believe her “no” meant “no.”

Thompson was part of pep band at the start of her freshman year, and she offered a ride from the Ford Center to an older student who didn’t have his own car. Nothing happened then, but she brought him home a second time.

He seemed a little creepy and controlling then, but Thompson didn’t think much of it before winter break. She suffered a severe injury and left school for a semester, and when she came back in the fall, he starting stalking and harassing her.

“He’d follow me even though he had no reason to,” Thompson said. “He would mention things casually about my life that you would only know if you were either really close or watching me.”

She said the stalker spent weeks of driving in circles around her apartment and trying to insert himself into her life. The guy waited for her while she went into the bathroom by The Loft.

“I went into the bathroom, and I didn’t want to come out,” Thompson said. “He called me and texted me repeatedly, saying, ‘I know you’re in there, are you in there alone? Hahaha, I could just come in.’ It terrified me.”

Eventually, Thompson alerted a friend, who came into the bathroom and walked out with her to ensure Thompson was safe.

She then went to Public Safety, where she said she was treated seriously.

“I felt supported by the university,” Thompson said. “I told them that I was feeling uncomfortable and didn’t know where to go. They told me the things I could do, such as go to a university official. But they couldn’t do anything (like arresting him) unless he actually attacked me because the university is a public space.”

When the university talked to Thompson’s stalker, he denied everything. But after he graduated, Thompson said he admitted to everything over messages and tried to act like everything between them was okay.

“I stopped going to band until he graduated,” Thompson said. “Band was my favorite thing before the wreck. I didn’t miss a single practice or a game, but then I completely stopped anything he was involved in. I was afraid, even after I’d gone with a university official. I was still afraid, and I wasn’t comfortably walking places by myself until he graduated.”

Thompson now feels like she has supportive friends that make her feel safe, and she’s grateful that the #MeToo movement is emphasizing the importance of consent.

“I wasn’t sure if it was my place to talk in the #MeToo movement and wasn’t sure if (my situation) would count, but the movement has affected me personally,” she said. “It meant something to me that people were able to stand up for themselves. Sometimes I blame myself, but I really didn’t want to leave somebody downtown without a ride. At the end of the day, I’m not the one that stalked somebody.”

Listen, don’t blame

Gender Studies Director Melinda Roberts said the #MeToo movement has brought unique change to the dialogue about sexual assault and consent.

“There have been movements before, but not exactly like this,” the associate professor of criminal justice said. “There was the No More campaign, which celebrities promoted and we tried to bring on campus through events like Walk a Mile (In Her Shoes)… The thing is, ‘No More’ was a collection of allies and victims. The difference with the #MeToo campaign is that it’s personal. They’re saying, ‘This is happening to me and I’m a human being.’”

Roberts said that difference has made it possible for people to see that sexual assault affects more individuals than realized before.

“When you stand up alone, there’s fear and victim blaming,” she said. “But when ten others stand up with you, they can really share their stories. When you see family and friends using the hashtag, it becomes personal, and I hope that motivates all people to have the ‘no more’ mentality.”

The best thing to do if someone shares their story with you is to listen, Roberts said.

“Just be supportive and ask if they need anything,” she said. “Tell them they didn’t deserve it. Sometimes that’s all you need to be a good responder.”

Roberts said she’s hopeful for a future where sexual violence against all persons is reduced.

“I hope all these people speaking out find peace, whether getting services like emotional or legal advocacy,” she said. “I hope they can transform themselves from victims to survivors. And for those who haven’t suffered, be supportive and intervene in situations to stop sexual assault.”

Alexsia Savage, a sophomore social work major, said it used to bother her to talk about when she was sexually assaulted, but over time and especially with the #MeToo movement, she’s felt more comfortable sharing.

Savage was 13 when she was drugged by a 20-year-old stranger in her own home and then raped. Her parents came home when a neighbor alerted them to a suspicious vehicle that pulled up in Savage’s driveway.

“It was December 27, 2011,” she said. “My friend said she invited this guy over…I woke up in my bed, and he was on top of me. I remember screaming for help…the next time I woke up, my dad was running in there, and my mom was there. My friend is crying, and she said she didn’t know him. The next thing I knew, I was in the hospital.”

Since then, Savage said she’s come to terms with what happened.

“People asked me, “Why didn’t you call your mom before that happened?’ and that made me think it was my fault. Maybe I should’ve called 9-1-1 or something,” she said. “But more people were supportive of me, and they were right there beside me when they found out about it.”

Savage said because of the #MeToo movement, she feels less nervous talking about her story.

“It doesn’t make me the only person that talks about it,” she said. “If I hear other people saying it, then I know I would be able to tell my story, too.”

Savage’s advice is to talk to a counselor or a professional about sexual assault right away.

“Don’t just sit there and talk in private with friends,” she said. “Don’t keep it a secret. It’s serious. Bring it to someone who knows what actions to take going forward.”

In the future, Savage hopes to get married and have children. She’s the first in her family to go to college, and she aspires to be a social worker who is empathetic to other children who go through abuse or assault.

“I feel like I could help them if they’re in the situation I was in,” Savage said. “I think I would know what to do. I overcame it.”

Jason Honesto contributed to this story.

Fast facts box:

Resources if you need support

Counseling Center 812-464-1867

Public Safety non-emergencies: 812-464-1845, emergencies: 812-492-7777

Title IX Coordinator (Melanie Kendrick) 812-465-1703

Dean of Students (Bryan Rush): 812-464-1862

Albion Fellows Bacon Center 812-424-7273

National Sexual Assault Hotline: 1-800-656-HOPE (4673)

YWCA: 812-422-1191

Holly’s House: 812-437-7233

Vanderburgh County Sheriff’s Office: 812-421-6200